Carroll C. Jones

Special to Smoky Mountain Times

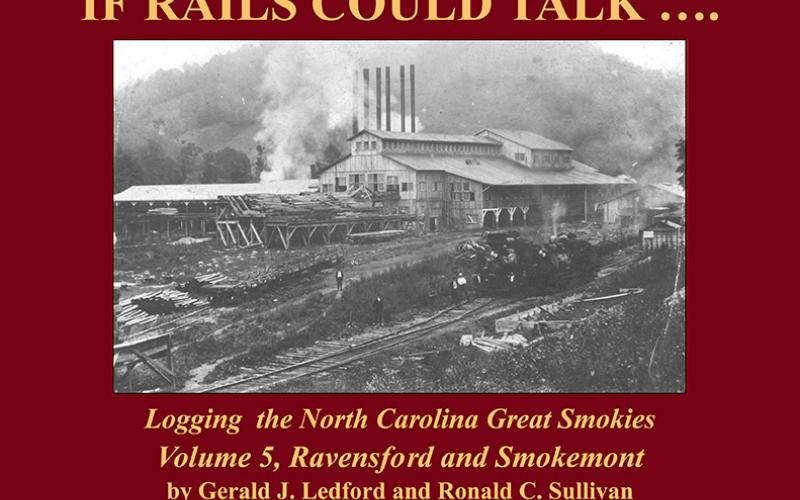

Gerald J. Ledford and Ronald C. Sullivan, local authors and historians, released a fifth railroading and logging book in their “If Rails Could Talk” series this summer.

It is titled “Volume 5, If Rails Could Talk: Ravensford and Smokemont” and highlights Swain County’s logging and sawmill operations at Ravensford and Smokemont in the early 20th century.

In Swain County, the book is available at Appalachian Mercantile, Uncle Bunky’s, Great Smoky Mountain Railroad Gift Shop and at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian. The book is also for sale at City Lights Bookstore in Sylva Malaprops in Asheville. Copies are also available online at The Tarheel Press.

The Foreword to “Volume 5, If Rails Could Talk: Ravensford and Smokemont” was contributed by Carroll C. Jones. A perusal of this brief introductory to the new book will give readers a glimpse into the subject matter and a clue about what Ledford, Sullivan, and those rails have been “talking” about.

In the last two decades of the 19th century, the railroad was finally able to wind and climb its way into Western North Carolina.

Immediately thereafter, remote timber resources of the Appalachian’s Blue Ridge Mountains became accessible and vulnerable to wealthy capitalists in search of virgin forests to support their relentless pursuits for financial gain.

Vast stands of spruce and hardwood trees, where once the Cherokee Indians prowled, were now a valuable treasure sought by logging companies.

However, it was no simple matter to “get out” this timber. The logging concerns had to make significant investments in equipment and labor to construct railroads through the wilderness.

It was not long before standard and narrow-gauge rails penetrated the deepest valleys and coves, bridged watery ravines, and ascended to the highest mountain crests. Woodsmen, living in primitive forest camps, were then able to “fell” the trees and cut them into logs using crosscut saws and axes.

These huge logs were rigged to overhead skidder cables or attached to oxen teams and transported to the nearest rail points for loading onto railcars.

Sawmills to process the logs into useful wood commodities were located near the timber tracts of the largest logging operations. When the timber reached one of these sawmills—either by rail, oxen team, or water flume — the enormous logs were rendered into lumber or pulp wood.

These valuable products were then shipped by rail to customers outside of the mountains or, in the case of the pulp wood, to a mammoth pulp mill located at Canton, North Carolina, in the heart of the mountains.

Villages usually grew up and surrounded these sawmills where loggers, railroad men, sawyers, saw filers, stokers, mechanics, helpers, and other employees and their families lived and plied their trades.

It was not uncommon for the villages to include — in addition to employee housing — a hotel, post office, depot, commissary, school, church, meeting hall for social events, post office, barbershop, doctor, electrical service, and even telephones. Although the sawmill villages were not permanent, they sometimes existed for a decade or more and took on the look, feel, and utility of a small town in the midst of a wilderness.

Strong on history

Readers of “Volume 5, If Rails Could Talk” are presented with the histories and stories of Ravensford and Smokemont, two logging sawmill villages as described above.

Authors Gerald J. Ledford and Ronald C. Sullivan illuminate the fascinating accounts of each of these logging camps (located less than 5 miles apart in North Carolina’s Swain County) from their founding a year or two before 1920 until their demise in the late 1920s.

Just as they have done in the previous volumes of “If Rails Could Talk,” these gentlemen leave no small details untold, while spinning cultural and historical tales about the Ravensford and Smokemont enterprises.

Most readers will probably realize that the lands of the former Ravensford and Smokemont logging operations are now part of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park; but they will have little knowledge of how that came to be.

Park story included

In this volume, the authors shine a bright light on the early 20th-century period when the Tennessee and North Carolina park commissions and the National Park Service took dead aim at the magnificent forests along the mountain divide between western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee.

The subject private properties of this volume were caught up in a growing movement to form a national park, and you will learn all about the messy affair and the final fate of Ravensford and Smokemont.

Ledford and Sullivan, possessing very different backgrounds and expertise, team up to reveal every conceivable aspect of the history and operations linked to the two properties. We learn about the founders of the logging companies and many facets of these entrepreneurs’ businesses.

The lives and activities of workmen who cut down the trees, hauled them to the mills, and then cut them up into profitable products come to life before our very eyes. And we are educated about the railroads and steam-powered equipment that reached into Swain County’s rugged forests to access and retrieve the valuable timber growing there.

Sullivan, on the one hand, has used his research skills and business acumen to uncover many of the commercial details related to the ventures at Ravensford and Smokemont.

Included are explanations of how control of the timber tracts passed from the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indian to the eventual two logging companies — Parson’s Pulp & Lumber Company and the Champion Fibre Company.

Also, he has assembled and presented numerous maps that allow readers to grasp at a glance the locations and layouts of assorted places, railways, and territories discussed in the story’s narrative.

On the other hand, Ledford offers in generous doses an unsurpassed knowledge of western North Carolina logging and railroads. Many of the photographs that show actual locomotives and trains in operation, logging equipment, and trackage are from his personal collection.

Plenty of photos

Pictures of old logging engines presented herein are not simply identified as “old logging engines.” Ledford thoughtfully gives us the engines’ make, model, manufacturing number, ownership provenance, repairs made, engineers’ names, and on and on.

For those readers who might not be familiar with the Shay engines, for example, or how they were used, rest assured that you will become very familiar with these invaluable workhorse machines after reading this volume of “If Rails Could Talk.”

For several years, Sullivan, his wife, Marilyn, and Gerald Ledford hiked the old logging railroad paths connected to the Ravensford and Smokemont operations.

Readers are treated to photographs the trekkers took of the old grades as they exist today and many interesting things the loggers left behind. Their discoveries included mangled bedsprings and pot-bellied stoves at the original logging camp sites; broken parts from locomotive engines; abandoned rails and skidder cables; unidentified pieces of metal machinery; the remnants of timber trestles; and much more.

Beware — seeing these intriguing images of railroading artifacts is sure to arouse the amateur archaeologist in everyone.

Carroll C. Jones was born and raised in the mountains of Haywood County, North Carolina. He received a structural engineering degree from the University of South Carolina and worked for more than 30 years in the paper industry. Jones has written seven historical non-fiction and fiction books to date. His latest is titled, “Thomson’s Pulp Mill: Building the Champion Fibre Company at Canton, N.C.—1905 to 1908.”